Calico over Ethernet fabrics

This is the first of a few tech notes that I will be authoring that will discuss some of the various interconnect fabric options in a Calico Cloud network.

Any technology that is capable of transporting IP packets can be used as the interconnect fabric in a Calico Cloud network (the first person to test and publish the results of using IP over Avian Carrier as a transport for Calico Cloud will earn a very nice dinner on or with the core Calico Cloud team). This means that the standard tools used to transport IP, such as MPLS and Ethernet can be used in a Calico Cloud network.

In this note, I'm going to focus on Ethernet as the interconnect network. Talking to most at-scale cloud operators, they have converted to IP fabrics, and as will cover in the next blog post that infrastructure will work for Calico Cloud as well. However, the concerns that drove most of those operators to IP as the interconnection network in their pods are largely ameliorated by Project Calico, allowing Ethernet to be viably considered as a Calico Cloud interconnect, even in large-scale deployments.

Concerns over Ethernet at scale

It has been acknowledged by the industry for years that, beyond a certain size, classical Ethernet networks are unsuitable for production deployment. Although there have been multiple attempts to address these issues, the scale-out networking community has, largely abandoned Ethernet for anything other than providing physical point-to-point links in the networking fabric. The principal reasons for Ethernet failures at large scale are:

- Large numbers of end points 1. Each switch in an Ethernet network must learn the path to all Ethernet endpoints that are connected to the Ethernet network. Learning this amount of state can become a substantial task when we are talking about hundreds of thousands of end points.

- High rate of churn or change in the network. With that many end points, most of them being ephemeral (such as virtual machines or containers), there is a large amount of churn in the network. That load of re-learning paths can be a substantial burden on the control plane processor of most Ethernet switches.

- High volumes of broadcast traffic. As each node on the Ethernet network must use Broadcast packets to locate peers, and many use broadcast for other purposes, the resultant packet replication to each and every end point can lead to broadcast storms in large Ethernet networks, effectively consuming most, if not all resources in the network and the attached end points.

- Spanning tree. Spanning tree is the protocol used to keep an Ethernet network from forming loops. The protocol was designed in the era of smaller, simpler networks, and it has not aged well. As the number of links and interconnects in an Ethernet network goes up, many implementations of spanning tree become more fragile. Unfortunately, when spanning tree fails in an Ethernet network, the effect is a catastrophic loop or partition (or both) in the network, and, in most cases, difficult to troubleshoot or resolve.

While many of these issues are crippling at VM scale (tens of thousands of end points that live for hours, days, weeks), they will be absolutely lethal at container scale (hundreds of thousands of end points that live for seconds, minutes, days).

If you weren't ready to turn off your Ethernet data center network before this, I bet you are now. Before you do, however, let's look at how Project Calico can mitigate these issues, even in very large deployments.

How does Calico Cloud tame the Ethernet daemons?

First, let's look at how Calico Cloud uses an Ethernet interconnect fabric. It's important to remember that an Ethernet network sees nothing on the other side of an attached IP router, the Ethernet network just sees the router itself. This is why Ethernet switches can be used at Internet peering points, where large fractions of Internet traffic is exchanged. The switches only see the routers from the various ISPs, not those ISPs' customers' nodes. We leverage the same effect in Calico Cloud.

To take the issues outlined above, let's revisit them in a Calico Cloud context.

- Large numbers of end points. In a Calico Cloud network, the Ethernet interconnect fabric only sees the routers/compute servers, not the end point. In a standard cloud model, where there is tens of VMs per server (or hundreds of containers), this reduces the number of nodes that the Ethernet sees (and has to learn) by one to two orders of magnitude. Even in very large pods (say twenty thousand servers), the Ethernet network would still only see a few tens of thousands of end points. Well within the scale of any competent data center Ethernet top of rack (ToR) switch.

- High rate of churn. In a classical Ethernet data center fabric, there is a churn event each time an end point is created, destroyed, or moved. In a large data center, with hundreds of thousands of endpoints, this churn could run into tens of events per second, every second of the day, with peaks easily in the hundreds or thousands of events per second. In a Calico Cloud network, however, the churn is very low. The only event that would lead to churn in a Calico Cloud network's Ethernet fabric would be the addition or loss of a compute server, switch, or physical connection. In a twenty thousand server pod, even with a 5% daily failure rate (a few orders of magnitude more than what is normally experienced), there would only be two thousand events per day. Any switch that can not handle that volume of change in the network should not be used for any application.

- High volume of broadcast traffic. Since the first (and last) hop for any traffic in a Calico Cloud network is an IP hop, and IP hops terminate broadcast traffic, there is no endpoint broadcast network in the Ethernet fabric, period. In fact, the only broadcast traffic that should be seen in the Ethernet fabric is the ARPs of the compute servers locating each other. If the traffic pattern is fairly consistent, the steady-state ARP rate should be almost zero. Even in a pathological case, the ARP rate should be well within normal accepted boundaries.

- Spanning tree. Depending on the architecture chosen for the Ethernet fabric, it may even be possible to turn off spanning tree. However, even if it is left on, due to the reduction in node count, and reduction in churn, most competent spanning tree implementations should be able to handle the load without stress.

With these considerations in mind, it should be evident that an Ethernet connection fabric in Calico Cloud is not only possible, it is practical and should be seriously considered as the interconnect fabric for a Calico Cloud network.

As mentioned in the IP fabric post, an IP fabric is also quite feasible for Calico Cloud, but there are more considerations that must be taken into account. The Ethernet fabric option has fewer architectural considerations in its design.

A brief note about Ethernet topology

As mentioned elsewhere in the Calico Cloud documentation, since Calico Cloud can use most of the standard IP tooling, some interesting options regarding fabric topology become possible.

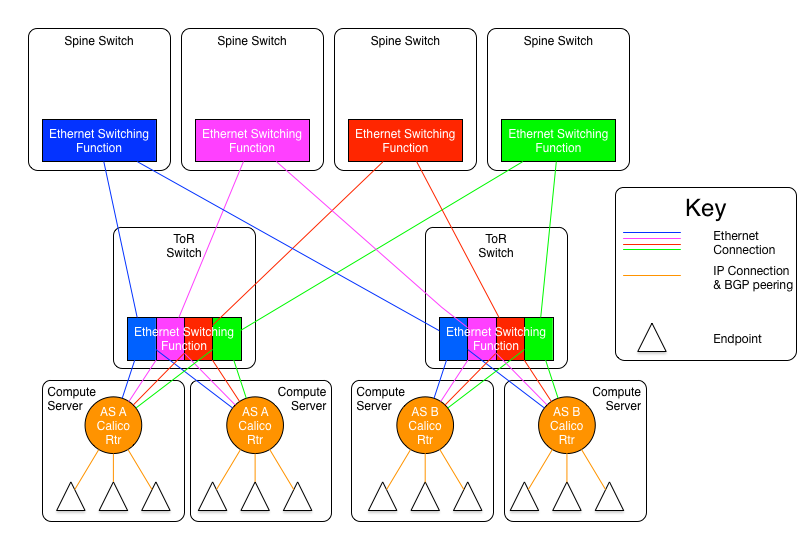

We assume that an Ethernet fabric for Calico Cloud would most likely be constructed as a leaf/spine architecture. Other options are possible, but the leaf/spine is the predominant architectural model in use in scale-out infrastructure today.

Since Calico Cloud is an IP routed fabric, a Calico Cloud network can use ECMP to distribute traffic across multiple links (instead of using Ethernet techniques such as MLAG). By leveraging ECMP load balancing on the Calico Cloud compute servers, it is possible to build the fabric out of multiple independent leaf/spine planes using no technologies other than IP routing in the Calico Cloud nodes, and basic Ethernet switching in the interconnect fabric. These planes would operate completely independently and could be designed such that they would not share a fault domain. This would allow for the catastrophic failure of one (or more) plane(s) of Ethernet interconnect fabric without the loss of the pod (the failure would just decrease the amount of interconnect bandwidth in the pod). This is a gentler failure mode than the pod-wide IP or Ethernet failure that is possible with today's designs.

A more in-depth discussion is possible, so if you'd like, please make a request, and I will put up a post or white paper. In the meantime, it may be interesting to venture over to Facebook's blog post

on their fabric approach. A quick picture to visualize the idea is shown below.

I am not showing the end points in this diagram, and the end points would be unaware of anything in the fabric (as noted above).

In the particular case of this diagram, each ToR is segmented into four logical switches (possibly by using 'port VLANs'), 2 and each compute server has a connection to each of those logical switches. We will identify those logical switches by their color. Each ToR would then have a blue, green, orange, and red logical switch. Those 'colors' would be members of a given plane, so there would be a blue plane, a green plane, an orange plane, and a red plane. Each plane would have a dedicated spine switch. and each ToR in a given spine would be connected to its spine, and only its spine.

Each plane would constitute an IP network, so the blue plane would be 2001:db8:1000::/36, the green would be 2001:db8:2000::/36, and the orange and red planes would be 2001:db8:3000::/36 and 2001:db8:4000::/36 respectively. 3

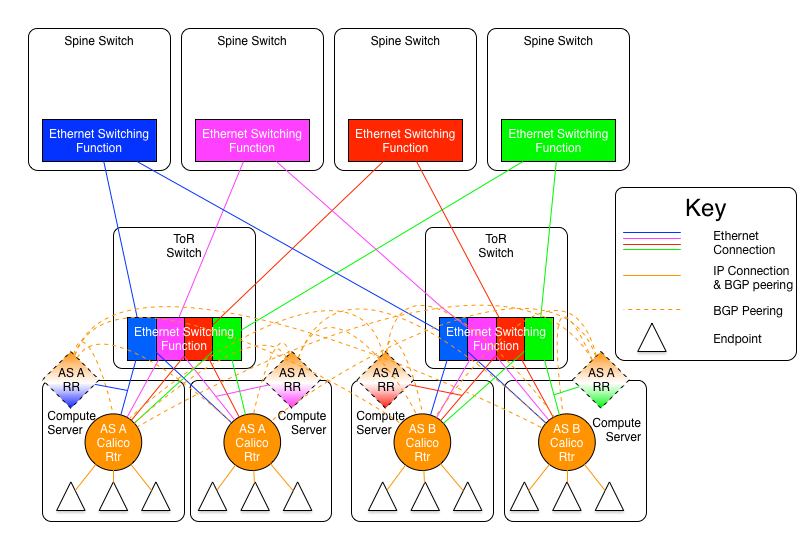

Each IP network (plane) requires its own BGP route reflectors. Those route reflectors need to be peered with each other within the plane, but the route reflectors in each plane do not need to be peered with one another. Therefore, a fabric of four planes would have four route reflector meshes. Each compute server, border router, etc. would need to be a route reflector client of at least one route reflector in each plane, and very preferably two or more in each plane.

A diagram that visualizes the route reflector environment can be found below.

These route reflectors could be dedicated hardware connected to the spine switches (or the spine switches themselves), or physical or virtual route reflectors connected to the necessary logical leaf switches (blue, green, orange, and red). That may be a route reflector running on a compute server and connected directly to the correct plane link, and not routed through the vRouter, to avoid the chicken and egg problem that would occur if the route reflector were "behind" the Calico Cloud network.

Other physical and logical configurations and counts are, of course, possible, this is just an example.

The logical configuration would then have each compute server would have an address on each plane's subnet, and announce its end points on each subnet. If ECMP is then turned on, the compute servers would distribute the load across all planes.

If a plane were to fail (say due to a spanning tree failure), then only that one plane would fail. The remaining planes would stay running.